By Jessica English, CD/BDT(DONA), LCCE, FACCE

The research on doulas is solid. Doulas improve outcomes for both parents and babies. Over the next six months, this blog will examine the six documented benefits of having a doula at one’s birth. We know that there are additional benefits along with these six published ones. This month, in our series: The Doula Difference, we discuss how doulas help in lowering cesarean rates. One of the most significant ways that doulas can have a positive impact on maternal-infant health is to assist in reducing the need for a cesarean section.

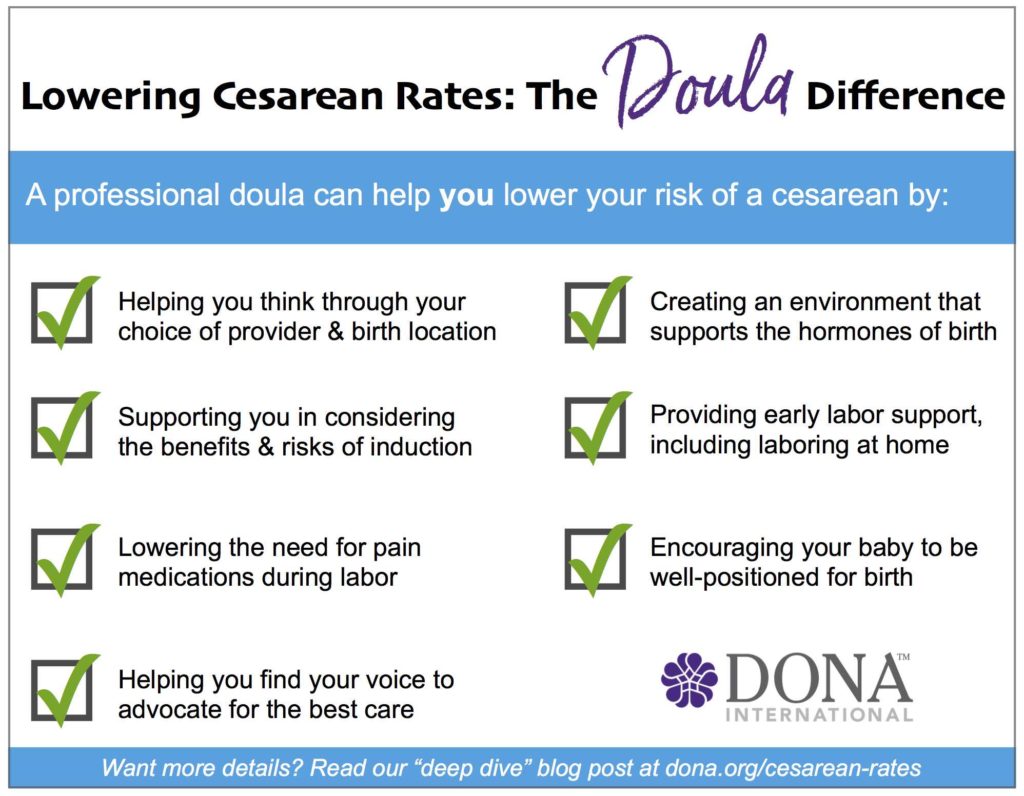

After reading Jessica English’s deep dive into how doulas help reduce cesarean rates for clients, consider using the accompanying graphic to help you spread the word and build your practice. You are free to use the graphic wherever you like. It can be a great marketing tool for you! Here are four ways you can utilize this informative post and graphic to build and promote your practice.

- Blog about using your skills to help your clients to avoid a cesarean and link back to this article.

- Share the graphic on your social media accounts and on your website, encouraging people to reach out to have your support at their birth.

- Share the cesarean rates of the hospitals and birth centers in your area and discuss how parents can make a choice that feels good to them.

- Interview a client who can share how you helped them to avoid a cesarean for your blog, website or social media accounts.

Look for future posts in this series and enjoy today’s post on “The Doula Difference: Lowering Cesarean Rates” as we close out World Doula Week. – Sharon Muza, DONA International Blog Manager

Introduction: Doulas Help Reduce Cesareans

Whether I’m talking with parents, training nurses and doctors to support physiologic birth, or advocating for insurance coverage for doulas, I often mention the impact doulas have on lowering cesarean rates. It’s a hot topic right now, as national attention has turned to reducing the current U.S. cesarean rate of 32.2 percent (Centers for Disease Control). Other countries have set their sights on similar reduction measures, as cesarean rates reach as high as 51.8% in Egypt and 55.6% in Brazil (Betrán et al. 2016), for example.

Depending on the study or review, doulas have been shown to reduce cesareans by anywhere from 28 percent (Hodnett et al., 2012) to 56 percent (Kozhimannil et al., 2016) for full-term births. When I share that information, people are usually impressed but also often look at me curiously and ask, “Why is that?” It’s a great question. In her blog post “The Evidence on Doulas,” Rebecca Dekker of EvidenceBasedBirth.com offers a great conceptual model for why continuous labor support improves outcomes. Aside from that model, I haven’t seen many explorations of exactly why doula support turns out to be so helpful. Let’s explore the doula difference and how it helps to reduce the risk of a cesarean birth.

Choosing a Birth Place and Provider

In a New York Times article last year, “Reducing Unnecessary C-Sections”, Tina Rosenberg offered this quiz:

What’s likely to be the biggest influence on whether you will have a C-section?

- Your personal wishes.

- Your choice of hospital

- Your baby’s weight.

- Your baby’s heart rate in labor

- The progress of your labor

According to research, the answer is B — your choice of a hospital. Other studies also show that choosing a birth center (Stapleton et al, 2013) or a home birth (Cheyney et al, 2014) reduces a woman’s risk of cesarean. Your personal provider’s cesarean rate also impacts whether or not you will have a cesarean birth.

So what does choosing a birth place or provider have to do with doulas? As part of our role prenatally, doulas help clients think through their choice of a provider and birth place. We ask about their relationship with their provider with questions like, “How is it going at your office visits?” or “How did it feel for you when your provider said that?” If clients tell us that they want to avoid a cesarean, a doula can suggest that they ask about their provider’s cesarean rate and if they’re having a hospital birth, the rate at that hospital. If there are concerns, doulas encourage our clients to explore their options and we support them if they decide to make a change. For clients who are motivated to avoid a cesarean birth, we can also share the research that shows that the provider and birth place a person chooses can make a difference.

Now that’s not to say that the doula tries to influence a client’s choice of providers. Guided by DONA International’s Standards of Practice and Code of Ethics for birth doulas, we respect a family’s right to make their own decisions about the best place to have their baby. The doula shouldn’t express an opinion, but we can definitely support families as they think through the decision on where to give birth and who will support them—decisions we know impact cesarean rates.

Avoiding Induction

Although there’s been some recent conversation in the medical world about how induction impacts cesarean rates, we do have studies that show that first-time mothers, in particular, are at higher risk of a cesarean when their labors are induced (Hannah et al., 1996, Kassab et al., 2011; Pavicic et al., 2009; Goer, 2012).

Doulas can help clients avoid induction by encouraging them to eat well and stay active throughout their pregnancies. We also help clients understand how waiting for labor to begin on its own can help them have a healthy birth (Lamaze International’s “Healthy Birth Practice #1: Labor Begins on Its Own” is a great evidence-based resource). Although the evidence does not usually support induction for a big baby, it’s a common reason given for induction. Doulas can connect families with research that they can talk about with their provider to understand why their provider might be recommending an approach to macrosomia that seems to conflict with recommendations from ACOG and other organizations.

If a woman’s provider suggests induction, we can encourage her to ask questions about whether the induction is medically necessary or elective. If it’s an elective induction, a doula might help her explore her feelings around that choice, connect her with information so she understands the process and the associated risks (including an increased risk of cesarean for first-time mothers), and remind her that the final decision on whether or not to be induced is hers to make. In my practice, we’ve sometimes worked with clients who believed that induction was a simple process and that their baby was likely to be in their arms the same day they were admitted to the hospital. Once they learn more about what induction entails and how long it can take, especially for a first birth, they’re sometimes inspired to talk with their provider about waiting for labor to begin on its own instead.

Avoiding or Delaying Epidurals

As with induction, there’s an ongoing debate among experts as to whether having an epidural in labor increases the risk of having a cesarean birth (Bannister-Tyrrell et al., 2014; Anim-Somuah, M. et al., 2011; Goer 2015). In reviewing the research, it seems that the strongest association between epidurals and cesarean birth is when the woman is having her first baby, and when the epidural is administered in early labor.

Hodnett’s meta-analysis shows that people who use a birth doula are nine percent less likely to use medication for pain relief. Doulas specialize in helping clients deal with the pain of labor with movement, massage, hydrotherapy, heat, cold and a variety of other non-medical tools. By using these methods with the support of their doula, people can delay or avoid using pain medication, which appears to have a positive impact on reducing cesarean rates.

Normalizing Hormonal Balance

When I first started teaching childbirth education 13 years ago, we didn’t hear much about the main hormones of labor: oxytocin, prolactin, beta-endorphins and catecholamines. Today, there’s been an explosion of interest in how these hormones influence the birth process. We have great resources to share with families and providers like Dr. Sarah Buckley’s recent “Hormonal Physiology of Childbearing: Evidence and Implications for Women, Babies, and Maternity Care,” available on the Childbirth Connection website.

In summary, the hormones that help move labor forward and relieve pain thrive on calm, privacy, and feelings of safety, connection, and nurture. Those are doula specialties! By offering continuous physical and emotional support, creating a “birth cave” in a hospital bathroom, or simply setting a calm, relaxing mood in the room, doulas can actually help labor work better. Continuous support is a critical component and supported by the research. This is one of the many reasons professional DONA International doulas do not leave a birth unless there’s a backup doula to take over! Reassurances about the normal sensations of labor help to lower the catecholamines (specifically adrenaline and noradrenaline), which can slow down or even stop labor progress. These seemingly soft touches that doulas bring to the birth space are actually designed to have a strategic, biochemical impact on the hormones of labor.

For clients who have a partner, doulas also work to help the partner be effective in their labor support role. We encourage emotional and physical connection between parents who love each other, or, for example, between a birthing woman and a grandmother who wants to nurture her baby through the birth process. Touch helps. Oxytocin, after all, is known as the cuddle hormone. By helping the partner feel comfortable and confident, we create the space for that nurture to happen.

Skilled, experienced doulas can also help bridge communication or ease any tensions between parents and their nurses, doctors or midwives. By helping everyone understand one another, the doula can help minimize any stress hormones that could interfere with labor progress.

Midwife Karen Laing recommends, “Keep the love high, and the stress low.” By managing the physical space and keeping tabs on the emotions of everyone in the room, masterful doulas can help manifest that vision—often without anyone else even realizing it’s happening. In turn, this helps labor progress and can reduce the risk of a cesarean section.

Laboring at Home

Studies show that delaying hospital admission until active labor can help reduce interventions, including cesarean birth. (Mikolajczyk et al, 2016, Kauffman et al, 2016). In their fact sheet on “Preventing Cesarean Birth,” the American College of Nurse Midwives recommends laboring at home until active labor. For low-risk women, ACOG’s new committee opinion on “Approaches to Limit Intervention During Labor and Birth” also states that admission to the hospital may be delayed until after the latent phase of labor (the latent phase ends when active labor begins, around six centimeters dilation).

That’s not to say that all the labor leading up to 6 cm isn’t hard work! It certainly can be challenging, and it’s sometimes many hours before someone in labor reaches that active labor mark (especially if they’re having their first baby). Who’s available to help hospital-birth families through early labor at home, or to support home birth families through the hours before their midwife arrives? This is another valuable role for the doula, of course. Doulas are available for phone support as labor begins and most are willing to meet clients at home to help clients through the early stages of labor. We help them stay comfortable, progress effectively, and recognize the eventual signs of strong, active labor. Rest, activity and comfort measures all come into play to manage these early hours of the birth process. In my experience, most first-time mothers estimate that they’re much further in labor than they really are. A doula can help a client in latent labor understand that although contractions feel strong it is still early, along with holding space for any disappointment or frustration that might come after hearing that news.

Doulas reassure and support partners, friends and family members during early labor at home too. Every seasoned doula has a story of a nervous loved one who was convinced that a baby was about to be born when the birthing parent was actually in very early labor. Because doulas are experienced and comfortable with the signposts of labor, contagious stress hormones are minimized for everyone. In their own comfortable space, partners can also rest during these hours of early labor, knowing that the woman is well cared for by the doula.

Doulas encourage, facilitate and model patience.

Malpositioned Babies

Before labor begins, doulas can connect clients with information and options that can help a breech baby turn into a head-down position. Breech position is a common reason for cesarean birth. When we help our clients learn about a position like the breech tilt or connect them with a local acupuncturist or chiropractor who might help a breech baby to turn, doulas may be helping those parents avoid a cesarean.

When a fetus stays “persistently posterior” during labor, the birthing parent is also significantly more likely to have a cesarean (Fitzpatrick et al. 2001, Cheng et al. 2006). When a baby is malpositioned, labors are also often longer and more challenging. Experts agree that we are seeing more malpositioned babies than in the past, with most theories centering on the likely cause as less activity and more sitting throughout pregnancy.

Fortunately for families, well-trained doulas have lots of tips and tricks for supporting these challenging births. Prenatally, doulas often encourage walking and pregnancy-specific exercises that may help a baby settle into an anterior position before labor begins. Doula trainings typically cover techniques that can help persistently posterior babies to turn in labor. Time, patience and strategic positioning are all part of the doula playbook. Along with demonstrating a variety of positions that can help a woman with a persistently posterior baby, in my doula workshops I also teach several rebozo techniques and a few peanut ball positions (Tussey et al. 2011, Tussey et al. 2015). Many doulas pursue advanced training in rebozo work, use of the peanut ball, or positioning approaches like Spinning Babies. Doulas see the challenges that can come with a malpositioned fetus and are often highly motivated to find as many techniques as possible for helping a fetus rotate into an ideal position. When babies don’t cooperate, skilled doulas also have techniques to optimize the chance that a posterior, occiput transverse or otherwise malpositioned baby can still be born vaginally.

Advocacy

Whenever I discuss the way doulas improve outcomes, I never pass up the chance to cover the doula’s advocacy role. We live in a society that often believes that technology is superior to nature. Not every hospital culture values the goal of intended vaginal birth, and in some facilities, providers may even joke about the benefits of a “vaginal bypass.” Liability concerns, staffing issues, available beds in labor and delivery, and provider patience may all play a role in when and whether a cesarean birth is recommended.

It’s outside the doula’s scope to offer an opinion on whether or not a cesarean birth is truly needed. In our advocacy role though, we can remind our clients of what they had hoped for their birth. We can make sure they fully understand what their provider is suggesting and why. Doulas can prompt parents to ask questions and consider options—including the option of waiting awhile longer to see how things progress. The DONA International Code of Ethics tells us that “the doula should make every effort to support maximum self-determination” of the client. That means that if a client makes an informed decision to decline a cesarean, in keeping with her ethical and legal rights, she may feel more comfortable and confident in that decision because she knows her doula supports that choice. (On the flip side, this implies as well, of course, that as doulas we would also fully support the informed choice to have a cesarean birth.)

This advocacy piece of our work can take some time for doulas to develop, especially given the nuances of navigating within complex health care settings. How do professional doulas lift their clients up to find their voices without upsetting nurses, doctors, and midwives? For birth doulas who want to work on this skill, DONA International offers a great webinar from Kim James of DoulaMatch.net on “Mastering the Doula’s Advocacy Role.” Whether through mentoring, courses, or self-study and experience, developing top-notch advocacy skills is a great career investment for doulas because it can make such an incredible difference in outcomes for families.

What do you think? Do these categories of “doula magic” resonate for you? Did I miss any areas where you think doulas have a positive impact on lowering cesarean rates? Have you seen direct results with your clients in any or all of these areas? Please leave me a comment below, I’d love to know your experiences and thoughts.

About Jessica English

Jessica English, CD/BDT(DONA), LCCE, FACCE, is a certified birth doula, postpartum doula and DONA approved birth doula trainer. She’s a certified childbirth educator with Lamaze International and a fellow of the Academy of Certified Childbirth Educators. In addition to her own doula work, training new doulas and running Michigan’s first and largest doula agency, Birth Kalamazoo, Jessica specializes in hands-on physiologic birth workshops for nurses and doctors. She is also the managing editor of the International Doula Magazine and owner of Heart | Soul | Business.

Jessica English, CD/BDT(DONA), LCCE, FACCE, is a certified birth doula, postpartum doula and DONA approved birth doula trainer. She’s a certified childbirth educator with Lamaze International and a fellow of the Academy of Certified Childbirth Educators. In addition to her own doula work, training new doulas and running Michigan’s first and largest doula agency, Birth Kalamazoo, Jessica specializes in hands-on physiologic birth workshops for nurses and doctors. She is also the managing editor of the International Doula Magazine and owner of Heart | Soul | Business.

References

Betrán, A. P., J. Ye et al. (2016). “The Increasing Trend in Caesarean Section Rates: Global, Regional and National Estimates: 1990-2014.” PLoS One, Volume 11, Issue 2.

Hodnett, E. D., S. Gates, et al. (2012). “Continuous support for women during childbirth.” Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews: CD003766.

Kozhimannil, K.B., R. R. Hardeman, et al. (2016). “Modeling the Cost-Effectiveness of Doula Care Associated with Reductions in Preterm Birth and Cesarean Delivery.” Birth, Volume 43, Issue 1.

University of Minnesota (2016). “Study: Doula care is cost-effective, associated with reduction in preterm and cesarean births.”

Dekker, R. (2013). “The Evidence on Doulas.” EvidenceBasedBirth.com.

Rosenberg, T. (2016). “Reducing Unnecessary C-Section Births.” New York Times, January 19, 2016.

Stapleton, S.R., Osborne, C. et al (2013). “Outcomes of Care in Birth Centers: Demonstration of a Durable Model.” Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health, Volume 58, Issue 1.

Cheyney, M., M. Bovbjerg et al. (2014). “Outcomes of Care for 16,924 Planned Home Births in the United States: The Midwives Alliance of North America Statistics Project, 2004 to 2009.” Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health, Volume 59, Issue 1.

Hannah M.E., C. Huh et al (1996). “Postterm pregnancy: putting the merits of a policy of induction of labor into perspective.” Birth Volume 23, Issue 1.

Kassab A., A. Tucker et al. (2011). “Comparison of two policies for induction of labour postdates.” Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Volume 31, Issue 1.

Pavicic H., K. Hamelin et al (2009). “Does routine induction of labour at 41 weeks really reduce the rate of cesarean section compared with expectant management?” Journal of Obstrics & Gynaecology Canada, Volume 31, Issue 7.

Goer, H. (2012). “Elective Induction at Term Reduces Perinatal Mortality Without Increasing Operative Delivery? Looking Behind the Curtain.” Science & Sensibility, May 28, 2102.

Bannister-Tyrrell, M., Ford, J. B. et al. (2014). “Epidural analgesia in labour and risk of caesarean delivery.” Paediatric Perinatal Epidemiology, Volume 28, Issue 5.

Anim-Somuah, M., Smyth, R. M. et al. (2011). “Epidural versus non-epidural or no analgesia in labour.” Cochrane Database of Systemic Reviews: CD000331.pub3

Goer, H. (2015). “Epidurals: Do They or Don’t They Increase Cesareans?” Science & Sensibility, January 26, 2015.

Buckley, S. J. (2015). “Hormonal Physiology of Childbearing: Evidence and Implications for Women, Babies, and Maternity Care.” Childbirth Connection Programs, National Partnership for Women & Families.

Mikolajczyk R., J. Zhang et al. (2016). “Early versus Late Admission to Labor Affects Labor Progression and Risk of Cesarean Section in Nulliparous Women,” Frontiers in Medicine, published online June 27, 2016.

Kauffman E., V. L. Souter et al. (2016). “Cervical Dilation on Admission in Term Spontaneous Labor and Maternal and Newborn Outcomes.” Obstetrics & Gynecology, Volume 127, Issue 3.

American College of Nurse-Midwives (2012). “Share with Women: Preventing Cesarean Birth.” Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health, Volume 57, Issue 4.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (2017). “Approaches to limit intervention during labor and birth.” Committee Opinion No. 687. Obstetrics and Gynecology, Volume 129:e20-8.

Fitzpatrick, M., K. McQuillan et al. (2001). “Influence of persistent occiput posterior position on delivery outcome.” Obstetrics and Gynecology, Volume 98, Issue 6.

Cheng, Y.W., B.L. Shaffer et al. (2006). “Associated factors and outcomes of persistent occiput posterior position: A retrospective cohort study from 1976 to 2001.” Journal of Maternal-Fetal & Neonatal Medicine, Volume 19, Issue 9.

Tussey, C., M. Botsios (2011). “Use of a Labor Ball to Decrease the Length of Labor in Patients Who Receive an Epidural.” Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic & Neonatal Nursing, Volume 40, Issue s1.

Tussey, C.M., Botsios E. et al. (2015). “Reducing Length of Labor and Cesarean Surgery Rate Using a Peanut Ball for Women Laboring with an Epidural.” The Journal of Perinatal Education, Volume 24, Issue 1

Trackbacks/Pingbacks